Medieval herbals for botanical bookworms

Although books might not be front of mind when you think of the Royal Botanic Garden, Australia’s oldest botanical library is tucked away in the Garden’s Robert Brown Building on Mrs Macquaries Road.

One of Sydney’s best-kept botanical secrets, the Daniel Solander Library was established in 1852, the same year as London’s Kew Gardens Library. Some of our collection’s most intriguing books about plants are the Medieval medicinal ‘herbals’, John Gerard's The Generall Historie of Plantes; Nicholas Culpeper’s Complete Herbal; and Dioscorides' De materia medica.

In days gone by, Western medical practices required skills and remedies that we don’t associate with contemporary doctors and pharmacists, making herbals fascinating records of culture, customs, time and place. Let's take a look at how herbals evolved…

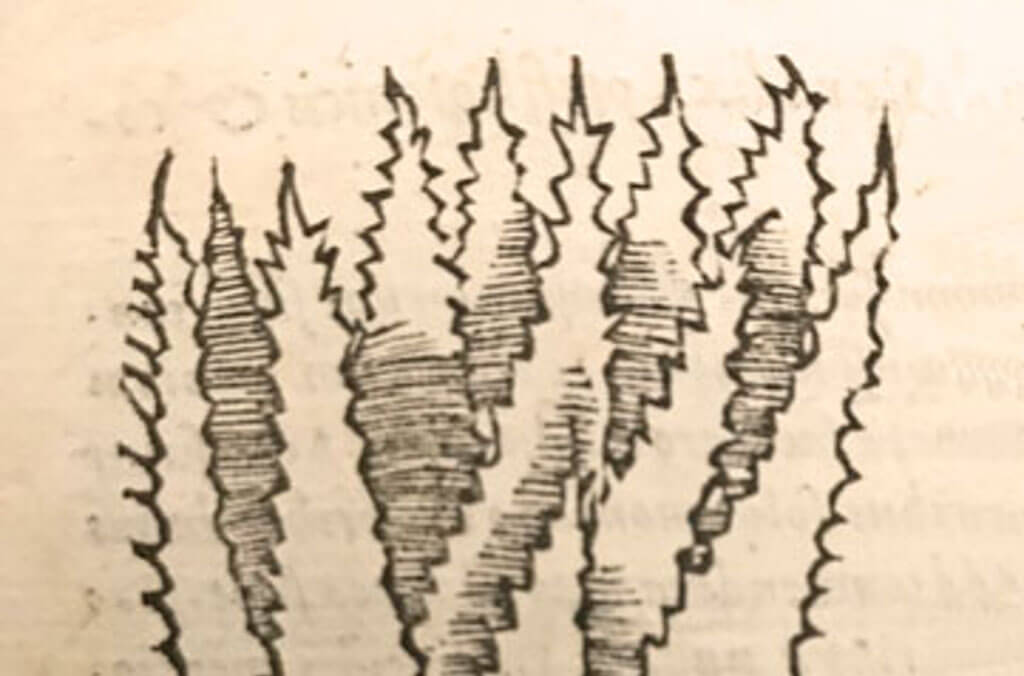

The Generall Historie of Plantes by John Gerard

The true forme of the Clove tree. Grown in Zeilan (Sri Lanka), Java and the Moluccas, in addition to remedies, Gerard describes beating the tree to harvest the buds. Image: Daniel Solander Library.

Physicians and apothecaries consulted the herbals when seeking information about identifying, gathering, and preparing medicinal herbs for specific illnesses. Not just confined to plants, cures also included minerals, gems and animals. Predating scientific botany and rationalism (knowledge gained by reason), which emerged during the Enlightenment (1685-1815), medieval herbals often associated plants with deities and planets. Because people believed that the features of the natural world were made of the flesh of gods, medicinal plants were inextricably linked with religion and the supernatural.

Jaocb Meydenbach's Hortus Sanitatis – The Garden of Health (1491)

Narcissus with homunculus (Latin: little people) With 1,073 woodcuts, Hortus Sanitatis was the most prolifically illustrated Medieval herbal. Image: Daniel Solander Library’s Kinnaird Collection

Where was the medicinal plant knowledge kept before there were books?

Before the invention of the printing press, knowledge of plant medicines was recorded in manuscripts by scribes and carved on stone and clay tablets. However, humanity has not always held its knowledge using the written word. Before writing, knowledge was (and still is in some cultures) passed down orally among the cunning folk, medicine men, shamans and knowledge keepers of the world’s villages, clans and tribes.

Singing to country

The Aboriginal Peoples of central Australia have engaged in the ceremonial practice of singing to country for thousands of years. Unlike a herbal that provides instructions for extracting specific therapeutic components from plants, singing to country is a mutually beneficial vibrational exchange that ensures the ongoing spiritual and physical health of the Elders, the bush medicines, their Peoples and all that is associated with them.

Looking further afield, Rongoā Māori knowledge is held orally in New Zealand; African nations have a strong, ongoing oral tradition of plant-based medicine, as do many other cultures. Early written references to herbal medicines in South America, India, China and Egypt all have their origins in oral traditions.

Statuette of Anubis, ancient Egyptian god of the afterlife. 332–30 B.C. Ptolemaic Period. Image: Metropolitan Museum of Art

Ancient Egyptian healing beyond the grave

One of the world's oldest extant records of herbalism, the Ebers Papyrus (1550 BC), is held in the University of Liepzig’s Library. It records information thought to have been handed down orally at least 500-2000 years before it was written. The papyrus made its way into European hands in 1872 when it was purchased in Luxor by the German Egyptologist George Ebers. The 20-metre scroll was reputedly found at the feet of a statue of Anubis, the ancient Egyptian god who presided over embalming and burial chambers.

The Egyptians honoured their dead with complex funerary rites, entombing them with all that was needed to live well in the afterlife. The Papyrus’ placement at Anubis’ feet may have been an offering to ensure the healing of the dead. The scroll comprised 100 pages with 811 prescriptions that included poultices, decoctions, gargles, snuffs, ointments, enemas, fumigations and inhalations made with honey and many plants known to us today including: Linseed, Barley, Lettuce, Mint, Grape, Poppy, Juniper, and Onion.

Also described were the three types of ancient Egyptian healers: physicians, surgeons, and sorcerers. Sorcerors were thought to be able to expel the spirits that were the cause of illness. The scroll also contained spells and incantations for this purpose, highlighting the importance of both spiritual and physical wellbeing in Egyptian culture.

Although earlier fragments of other documents devoted to medicinal plants exist, the first Western herbal to survive intact was Dioscorides’ De materia medica, a comprehensive reference containing information about 500 plants. The Daniel Solander Library has a copy dating back to the 1500s in its collection.

A soldier during Nero’s reign, Dioscorides travelled widely throughout the Roman Empire, picking up knowledge of herbal remedies as he went. He was an all-business kind of man who approached his work systematically; if a plant held no therapeutic value, he simply ignored it. He also employed what was considered in its day to be an idiosyncratic filing system, shunning alphabetical order and instead grouping plants based on like properties, form and origin, similar to the system later deployed by Linnaeus.

The written form gave the precious herbal knowledge Dioscorides had collected mobility. When pagan Greek scholars fled Emperor Constantine’s rule in Byzantium with De materia medica in their possession, it was translated into Syriac. It was later translated into Turkish, Hebrew, Arabic and Persian and became an indispensable reference for Muslim physicians.

The mobility of Dioscorides’ herbal led to the realisation that although most people are of the same anatomical design, plants and their medicinal properties are not the same everywhere. This revelation foreshadowed the separation of medicine from botany. De materia medica was eventually translated into Latin, English, French, German, Italian, Spanish and Bohemian and was still in print in the 1970s.

References & further reading

An illustrated history of the Herbals (1977), Frank J Anderson.

The Art of Botanical Illustration (1994), Wilfred Blunt & William T Stearn.

Herbals: The Connection Between Horticulture and Medicine (2003), Jules Janick.

Demystifying Rongoā Māori: Traditional Māori Healing (2008), Best Practice Journal.

Learn more about medicinal plants

- Explore the Daniel Solander Library’s online catalogue to check out the herbals in our collections; the Library is open by appointment. Please note, the Library's copy of Culpeper's Complete Herbal is temporarily unavailable for viewing.

- Book an Aboriginal Heritage Tour, then have a wander in the Herb Garden, which has interpretive signage explaining the historical uses of its plants.

- Listen to our Branch Out podcast episode No Plants No Medicine.

Related stories

Flora Deverall, 90, is a volunteer guide at the Botanic Gardens of Sydney and a powerful example of the role of passion, purpose, and plants in a remarkable life. We wanted to share her inspiring story for National Volunteer Week 2025.

Bunga Bangkai (Indonesian), Titan Arum or Amorphophallus titanum has the biggest, smelliest flower-spike in the world. It flowers for just 24 hours, once every few years… and in January 2025 one bloomed at the Royal Botanic Garden Sydney. Named Putricia by staff at the Botanic Gardens of Sydney, she quickly captivated people from all over the world, writes John Siemon, Director of Horticulture and Living Collections.

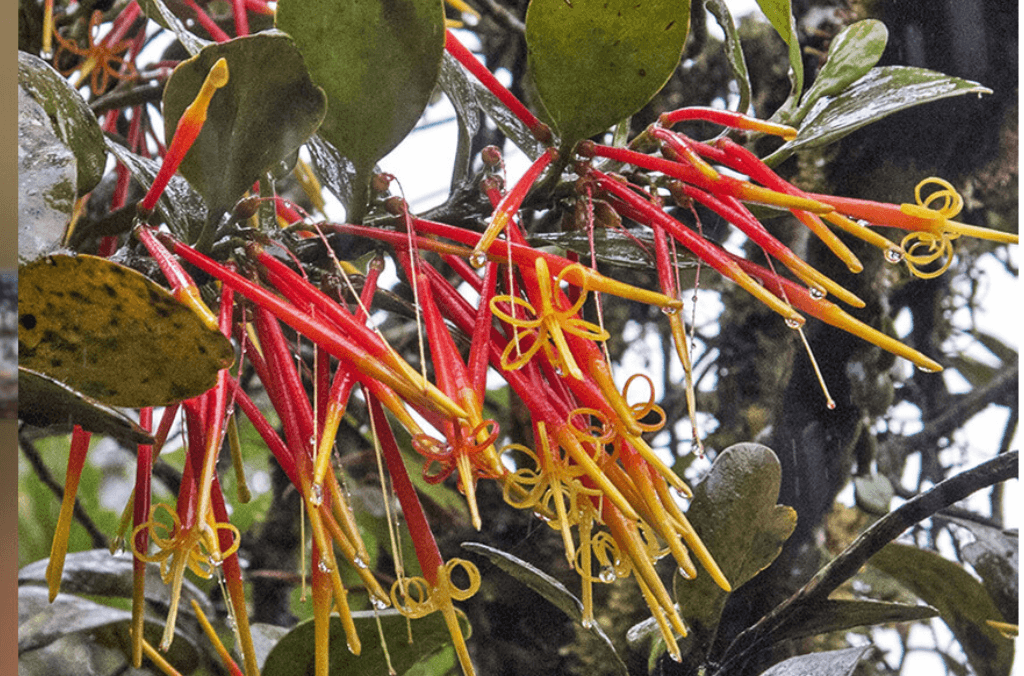

Mistletoe is in love potions, ancient medicines to ward off epilepsy and ulcers, and even a Justin Bieber Christmas song.