Mistletoe: a festive & freaky parasite

Mistletoe is in love potions, ancient medicines to ward off epilepsy and ulcers, and even a Justin Bieber Christmas song. But why are so many people throughout the ages fascinated by the mystery and magic of these paradoxical parasites?

To most people's surprise, our merry mistletoe is actually a parasite that grows on the branches or roots of other plants to steal nutrients and water. The bizarre adaptation started in Australia too – the true home of mistletoe with about 90 different sap-sucking species.

Listen to our Branch Out podcast with Systematic Botanist Dr Russell Barrett or continue reading below. You'll see that kissing under the mistletoe is the least interesting story about this bizarre group of parasitic plants.

Hungry for a host

When a mistletoe seed lands on a branch (we'll get to that part later) within days, a tiny tendril emerges, growing quickly as it secretes a cocktail of enzymes directly onto the outer layer of the branch.

Unable to resist the attack, the bark produces a small ulcer-like hole into which the tendril probes, seeking its way down into the sappy tree tissue until it hits the water and mineral-rich plumbing of the tree.

Some mistletoe species are very particular about who they attach themselves too. For example, in Australia we have a species that only grows on Banksia and one that only wants to call the salty mangrove branches home.

Mistletoe parasite

Amyema miquelii mistletoe seedling attaching to a tree branch.

Australian mistletoe magic

Systematic Botanist, Dr Russell Barrett from the Botanic Gardens of Sydney has a keen interest in these sap-suckers and has collaborated with international researchers to understand more about the origin of these parasitic predators.

“Mistletoe plants traditionally either belong to the Loranthaceae or the Viscaceae families and in Australia we have about 90 different species,” said Dr Barrett.

"Mistletoe are over 30 million years old and there has been a lot of debate about where they originally came from and how they are now found in so many different parts of the world."

Using DNA technology and fossil records, Dr Barrett's team found that the origin of mistletoe is in fact Australia, or at least the part of Australia that was attached to Gondwana.

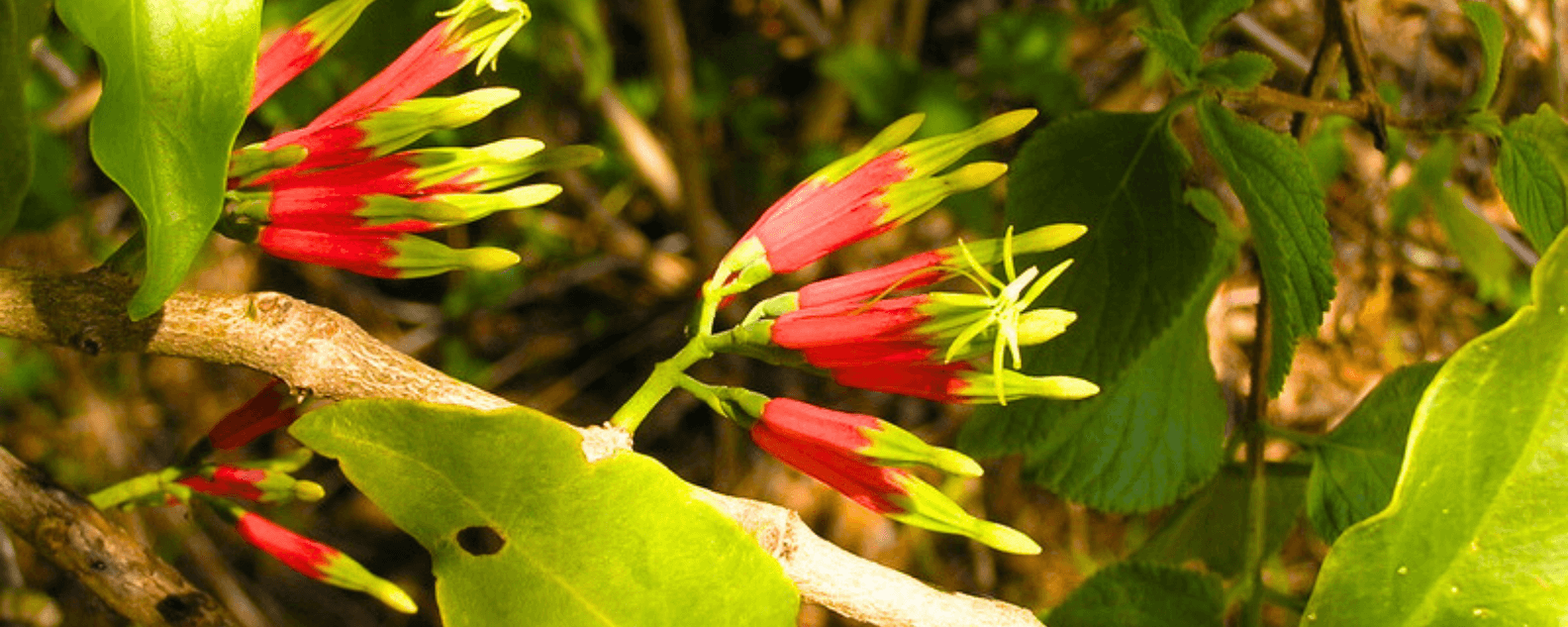

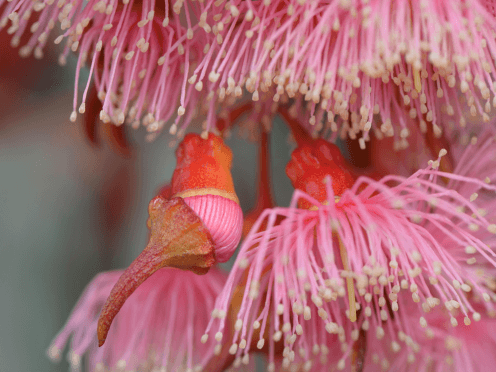

Amylotheca dictyophleba (Bush Mistletoe) flowering in summer

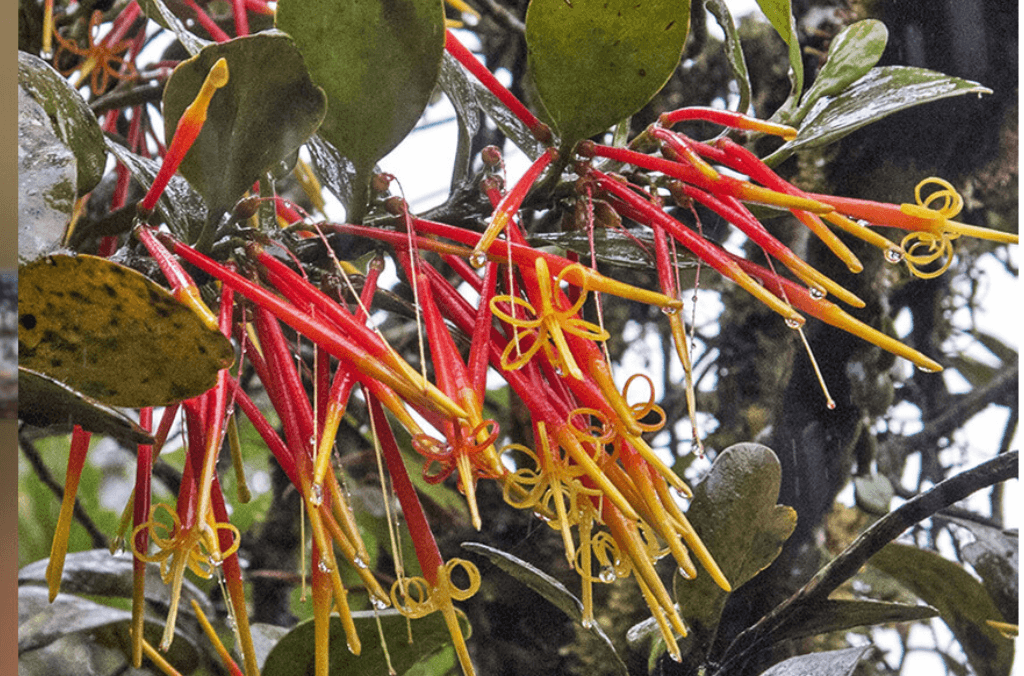

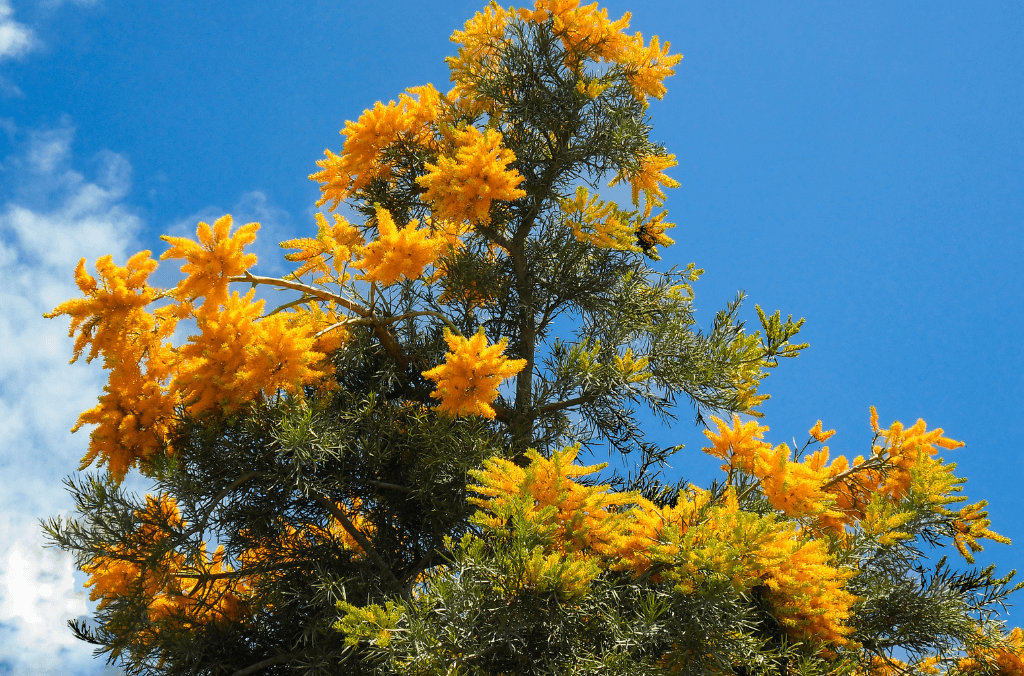

The oldest mistletoe surviving today is Nuytsia floribunda, which is found in Western Australia. It’s actually known as the Christmas tree because it blooms so dramatically in summer. The showy orange flowers have been likened to ‘a bushfire without smoke’.

It's a local legend for another reason too... This sap-sucker is one of two species that attaches itself to the underground roots of other plants. It has blades on its roots sharp enough to break skin and slice through underground cables!

"When they were running the first telephone lines from Perth to Geraldton across the sandplains where Nuytsia grows, they kept breaking and they had no idea why," said Dr Barrett.

A bit of digging quickly revealed that the beloved Christmas tree was mistakenly attaching itself to the telephone cables in search of a host with nutrients and water.

Systematic Botanist, Dr Russell Barrett at the Australian Botanic Garden Mount Annan

Tis' the season for symbiosis

As far as plants go, mistletoe is quite remarkable because it relies exclusively on birds to spread its seeds.

"The mistletoe bird feeds off the berries of the mistletoe plant, and in return for this constant food source, the birds have evolved to be the perfect carrier and distributor of the seeds within, since it eats the seeds and then deposits them on the branch of another tree, usually within minutes,” said Dr Barrett.

However, the mistletoe bird is relative newcomer and only arrived in Australia about one to two million years ago from Asia. So how did mistletoe make its way from Australia to the rest of the world?

"Mistletoe got to Asia from Australia somewhere in the order of about 25 million years ago during a time when Australia and Asia were still quite separated, but the first islands were being pushed up between them."

There were only pigeons and cuckoos in Australia around during this time and they are the only birds really capable of fly between 500-1000km.

The theory is that due to the high sugar content in mistletoe fruit, it's likely it sustained them on their long cross ocean voyages between Australia and Asia.

Mistletoe bird

First Nations mistletoe traditional uses

Mistletoe is most popularly known through its place in ancient legends and mythology, and its widespread use in folk medicine. Given it calls Australia home, it is also important to many First Nations people.

"For some First Nations people, mistletoe was primarily a source of food because their sticky fruits are sweet. The medical properties of particular species were even used to treat common colds," said Dr Barrett.

Mistletoe is is also very soft-stemmed and you can peel back its layers like an onion. This means they are very fire-sensitive and they act as an important indicator for the condition of country.

The Western Australian Christmas tree is particularly sacred to the Noongar Aboriginal people in Perth because it is a transit point for dead spirits and is intimately connected to the afterlife.

A Noongar elder explains that ‘A spirit sits on the tree until it flowers. Then the spirit moves on to the spirit world in conjunction with easterly winds and fire, which take the spirit out over the sea.’

Nuytsia floribunda, West Australian 'Christmas tree'

Kissing under the mistletoe origin

The plant’s parasitic nature is probably why people began to think mistletoe was special enough to kiss under in the first place. The earliest chapter in mistletoe folklore is said to come from Norse mythology.

The god Odin had a son Baldaur who was prophesied to die. Baldaur’s mother, Frigg, the goddess of love, then went to all the animals and plants of the natural world to secure an oath that they would not harm him.

However, Frigg forgot about the unassuming mistletoe, so the scheming god Loki made an arrow from the plant and saw that it was used to kill the otherwise invincible Baldaur.

In one version of the story, Frigg cried over the dart lodged in her dead son and the tears turned into berries that brought him back to life. In return to the miracle, Frigg declared mistletoe a symbol of love and vowed to plant a kiss on all those who passed beneath it.

If you find yourself underneath a mistletoe this holiday season, maybe instead of sharing a kiss, you might like to share a fun fact about them instead.

Subscribe to our Branch Out podcast

Hit play to listen to the Mistletoe: a festive and freaky parasite podcast episode with Dr Russell Barrett below or subscribe to the Branch Out podcast on your Apple or Android app.

Related stories

Three carnivorous plants to care for during the cooler seasons.

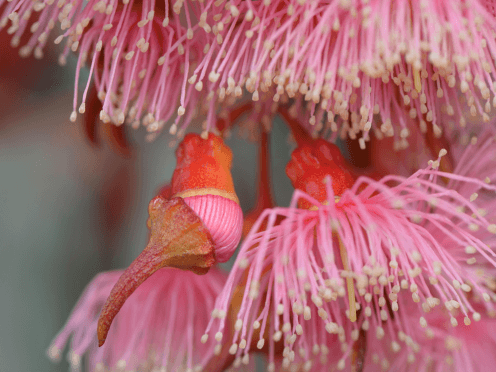

Eucalypts or gum trees are one of Australia’s most iconic plants. The scent of their oil alone evokes the bushland.

Eucalypts or gum trees are one of Australia’s most iconic plants. The scent of their oil alone evokes the bushland.