The life and legacy of Margaret Flockton

Quiet, serious and self-effacing Margaret Flockton is belatedly receiving recognition as among the ‘greats’ of botanical artists.

She was born to the task: her parents were both artists, her grandfather was a scientist (industrial chemist), and a more distant ancestor Dr George Young was the first curator of the famous Botanic Garden on the Caribbean island of St Vincent, in 1765.

She came into the world on 25 September 1861 at Leyton, England, the middle child in a well to-do family. Within four years her father had abandoned his well-paid occupation and indulged himself in his passion, art. Margaret said her own career as an artist began around this time, when a pencil was put in her hand at the age of three.

Her father had only modest success as an artist. Before Margaret reached her tenth birthday, the Flocktons were impoverished. They moved to cheaper accommodation in south Wales, where Margaret attended the Cardiff Science and Art School.

Margaret Flockton circa 1914.

Early years

Margaret’s parents were occasionally rescued by the final bequests of various rich relatives, and her art training continued. In her later teens she lived in ‘digs’, attending the Female School of Art in Bloomsbury (now part of Saint Martin’s College of Art & Design) and as one of the better students was sent to the Science and Art Department’s principal school at South Kensington, where she was awarded an Art Teacher Certificate in 1885. She was one of the first eight women in England to learn lithography.

In 1888 Margaret and her parents moved to Sydney by courtesy of an emigration opportunity, never to return to England. Her decade of intensive training at the highest levels in England meant that Margaret was the most thoroughly- trained female artist living in Australia.

Brachychiton by Margaret Flockton

Life in Australia

She quickly found work as a lithographer with several publishing companies in Sydney but she spent most of 1892 living with her younger sister and family in a booming gold-mining town in outback Queensland. Here she taught art, did a little painting ‘from nature’, and decided to change her direction in life.

She returned to Sydney and set about being a ‘fine artist’. She established a studio, used her impressive qualifications to teach art and joined the Royal Art Society of NSW where she exhibited 39 watercolour paintings at its showings from 1894 to 1901. Her still-life work was instantly recognised as outstanding.

Her sojourn in Queensland had inspired Margaret with a love of Australiana. She visited the Technological Museum in Sydney to paint the display of native flora and exhibited six of these watercolours, catalogued as ‘Australian Wild Flowers’.

One depicted the state’s official floral emblem, the Waratah, and was bought by the NSW Art Gallery; another was selected for inclusion in an album sent to Queen Victoria for her diamond jubilee.

Waratah Wildflower print circa 1905 by Margaret Flockton.

Commercial art

In the early 1900s Margaret briefly engaged with the world of commercial art. The American Tobacco Company advertised a series of twelve Australian wildflower lithographs by Margaret, offered as part of an intensive marketing campaign to encourage smoking (a habit not favoured by Margaret herself). These works were extremely popular with the public and were framed and hung on the walls of hundreds of homes around Australi

Catherine Wardrop of the Royal Botanic Garden Sydney says these wildflower lithographs show a great deal of hand rendering, hatching and cross-hatching on a half tone dot ground. As there is no evidence of the stone surface in these images, Catherine believes the four CMYK images were drawn from scratch directly onto metal plates, following tracings from original watercolours.

But although Margaret signed her lithographs, most of the company’s advertisements did not mention her name as the artist. The wildflower lithographs were also reproduced as a commercial postcard series, probably printed directly from photos of the paintings, with no extra interpretation from the artist.

Video courtesy of the Sydney Morning Herald: Rare botanical beauties rediscovered

Botanical illustrations

At the Technological Museum, Margaret came to the attention of its Curator, Joseph Maiden, who offered her a job as artist at the Sydney Botanic Garden (now called the Royal Botanic Garden Sydney). Aged forty, she began her work for him in 1901, and she retired at the age of sixty five, having executed more than two thousand scientifically-accurate drawings of Australia’s flora.

Margaret’s renditions of the Waratah and the Christmas Bush as scientific botanical drawings are just as artistic as her commercially- produced lithographs. Her scientific botanical drawings are retained within the archives at the Garden. On rare occasions a few are selected for display at relevant public exhibitions.

Her black and white work illustrates many botanical texts, especially Maiden’s two major works, The Forest Flora of New South Wales (1903-1924) and A Critical Revision of the Genus Eucalyptus (1903-1933), of which some later parts contain colour plates. An online version of both books is published on the University of Sydney Library website, with links to images of Margaret’s wonderful work.

Eucalyptus pilularis by Margaret Flockton.

Offset lithography

All of Margaret’s black and white printed works for the Forest Flora and Critical Revision projects were hand drawn by Margaret on lithographic stone. After tracings of line work were taken from original sketches and transferred onto the stone, drawing was done using greasy pencils and crayons.

According to Wikipedia’s discussion of lithography, the stone was then treated with a mixture of acid and gum arabic, ensuring that the portions not protected by the grease-based image would retain water when the stone was subsequently moistened. The damp sections of the stone would then repel the application of oil-based ink, which would stick only to the original drawing.

The ink would finally be transferred from the stone to a blank paper sheet, producing a printed page. Margaret’s early plates were almost certainly printed from the stone, with evidence of the unique texture the stone surface gave to tonal work. Over time this process developed into more mechanised offset lithography.

With offset lithography, images could be transferred from the stone to a rubber roller, and the printing would all be done from this cylinder being inked and offsetting a print each time it turned a full circle.

Acacia binervia by Margaret Flockton

Australia’s first female lithographer

Catherine Wardrop notes that in the Critical Revision the coloured plates appear to be photographically reproduced with the half tone dot system straight from coloured paintings, some of which are in the Gardens archive. Margaret also made several hundred quarto coloured drawings of Opuntia.

Some were published between 1911 and 1917 as illustrations for Maiden’s series ‘Prickly Pears of Interest to Australians’ in the Agricultural Gazette of New South Wales. La Mortola in Italy, the world’s leading authority on Opuntia, told Maiden in 1908 that ‘we cannot find an artist able to reproduce the plants as your artist does'.

Catherine Wardrop says that ‘the Opuntias seem to have each had their four individual half tone coloured plates (CMYK) hand worked by Margaret herself. The original drawings carry the full line work but only the basic colour information, which means Margaret completed the images fully only when the four colour plates were prepared for printing.

The prints carry her trademark sensitivity to form and line so, as she was Australia’s only female lithographer at this time, these glorious prints were an outstanding showcase for her skills. She handed the plates over to the government printing office only for the final pulling of the prints’.

Her legacy continues

In her private life in Sydney, Margaret lived with her parents. She was close to her sisters and for a period after her father’s death in 1901, her household became three-generational, with Margaret like a mother to her nieces and nephews. Somehow, although underpaid compared with her male colleagues, Margaret managed to save enough to buy her own modest cottage, ‘Tulagi’ at Tennyson, a harbourside suburb, where she resided after her mother’s death in 1917 until her own death on 12 August 1953, about six weeks before her 92nd birthday.

It took another fifty years before two botanical artists in Margaret’s former workplace – Catherine Wardrop and Lesley Elkan – rediscovered her, and championed her cause on International Women’s Day in 2003.

Their speech had an immediate impact and Margaret’s long period of neglect quickly ended. In 2004 the Friends of the Gardens and Botanic Gardens Trust initiated the Margaret Flockton Award for excellence in scientific botanical illustration, now in its 16th year.

2019 Margaret Flockton Award exhibition

Competing this year were 26 scientific botanical illustrators from 17 countries - Australia, USA, Canada, UK, Japan, Indonesia, Singapore, Italy, Portugal, Spain, Brazil, Mexico, Argentina, Colombia, Germany, Poland, and Turkey.

The artists have employed pencil, pen and ink, purely digital or a combination of digital and traditional media to illustrate the 44 contemporary illustrations entered. Plants showcased are of the common garden variety but also newly described species.

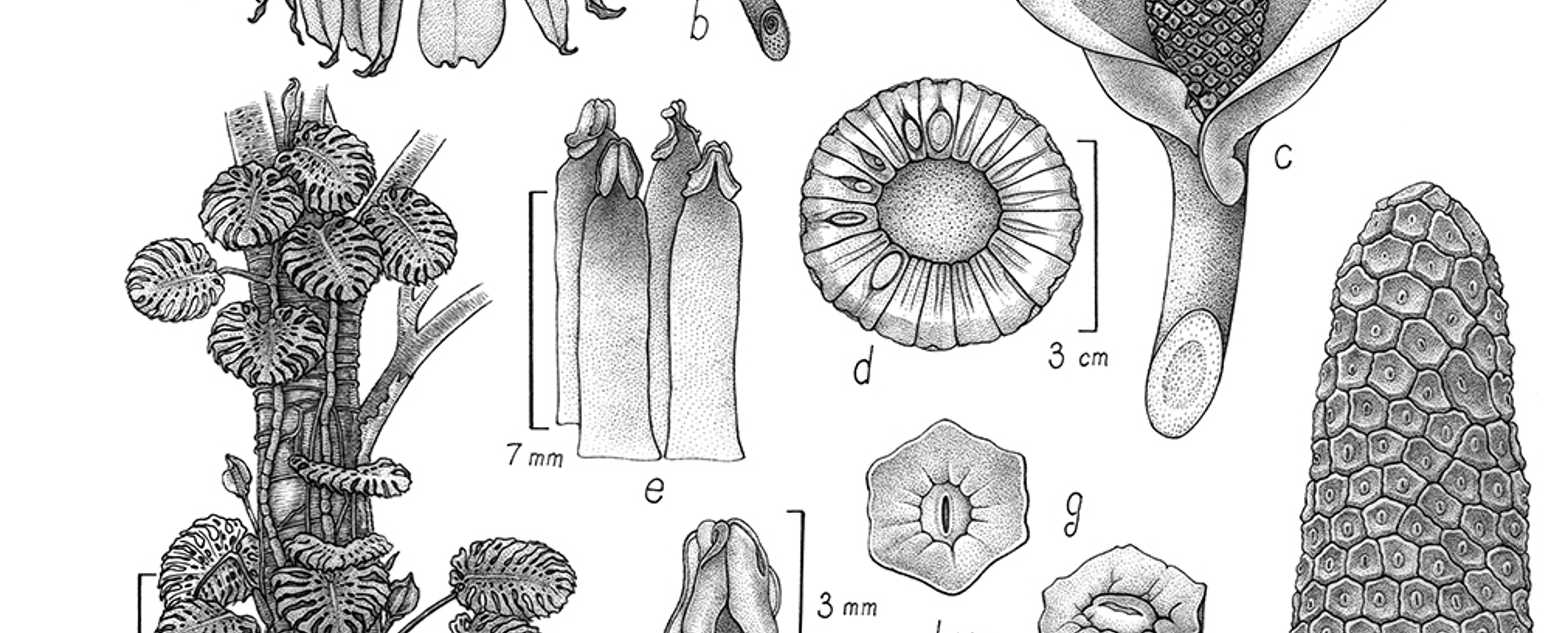

The winner of the 2019 Margaret Flockton Award was presented on the 30 March to Edmundo Saavedra from Mexico for his illustration of Monstera deliciosa (pictured below). All works will be on display in the Maiden Theatre at the Royal Botanic Garden Sydney until 14 April 2019.

2019 1st Prize: Monstera deliciosa by Edmundo Saavedra.

Following the exhibition at the Garden, the high quality giclée prints will once again be on display at the Australian Botanic Garden Mount Annan and the Blue Mountains Botanic Garden Mount Tomah.

Find more information about the Margaret Flockton Awards.

Article first published in The Botanic Artist as A Fragrant Memory by Louise Wilson.

Related stories

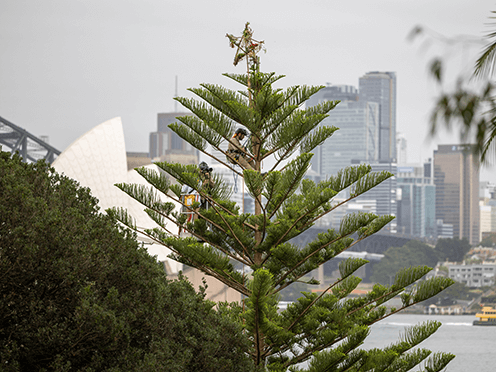

Discover the Royal Botanic Garden Sydney's very own "Christmas trees" - a festive trio of pretty pines from a lineage stretching all the way back to the time of the dinosaurs.

Flora Deverall, 90, is a volunteer guide at the Botanic Gardens of Sydney and a powerful example of the role of passion, purpose, and plants in a remarkable life. We wanted to share her inspiring story for National Volunteer Week 2025.

Bunga Bangkai (Indonesian), Titan Arum or Amorphophallus titanum has the biggest, smelliest flower-spike in the world. It flowers for just 24 hours, once every few years… and in January 2025 one bloomed at the Royal Botanic Garden Sydney. Named Putricia by staff at the Botanic Gardens of Sydney, she quickly captivated people from all over the world, writes John Siemon, Director of Horticulture and Living Collections.