Indigenous Australians base their seasons on changes in weather, plants and animals around them, and celestial patterns.

This can mean more or sometimes less than four seasons in a year. We call these observations ‘seasonal indicators’.

These seasonal indicators dictated the timing of movements of Aboriginal people from place to place, influenced their activities, the foods they ate and their cultural use of plants and other resources.

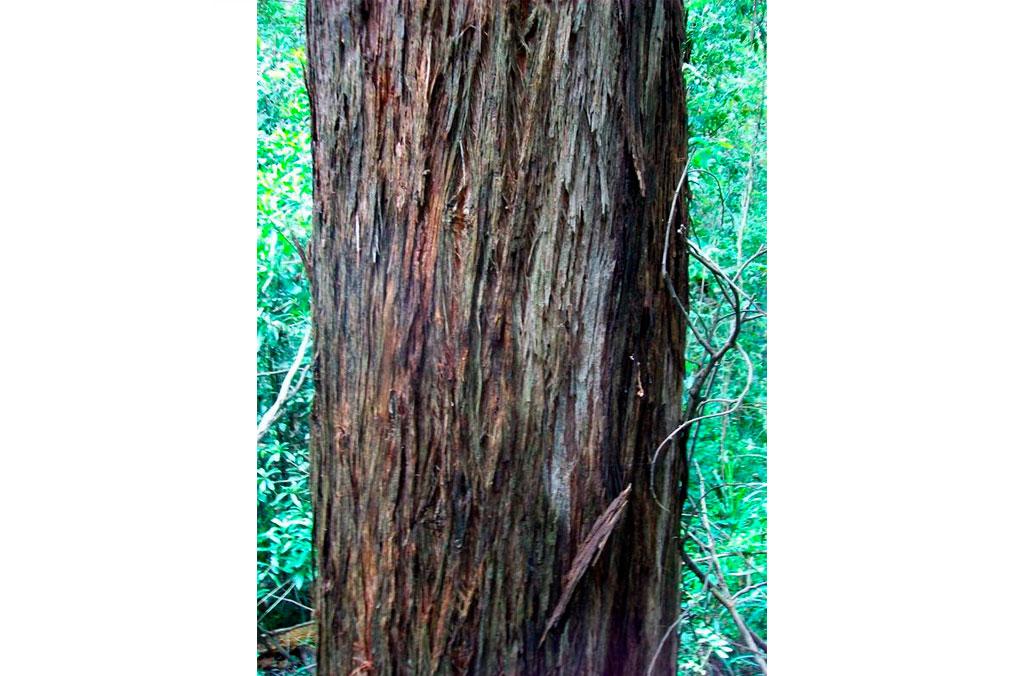

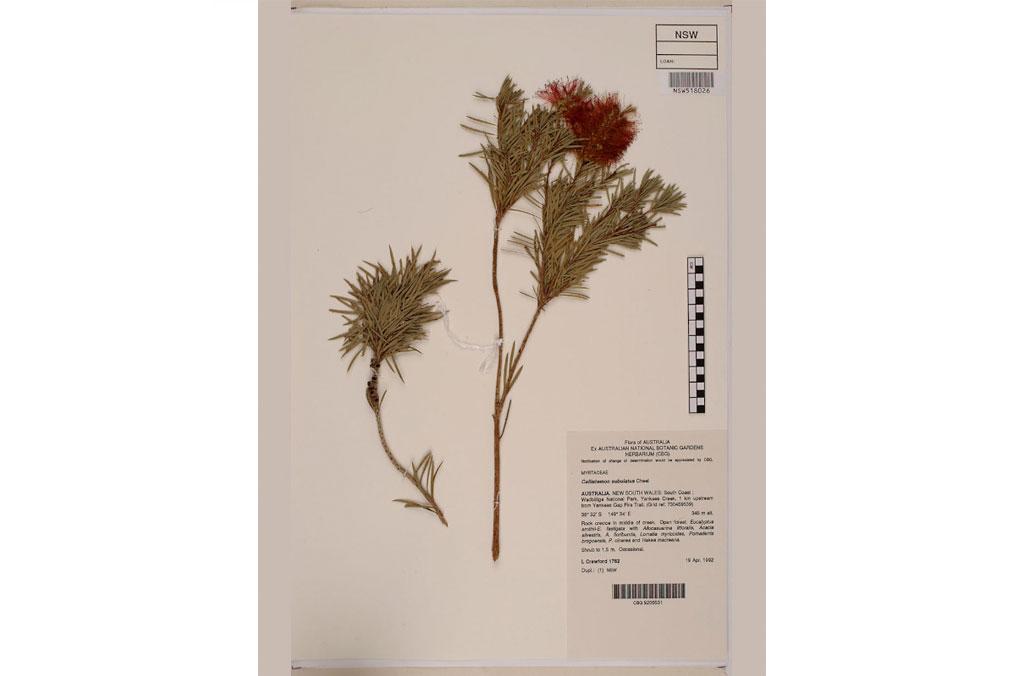

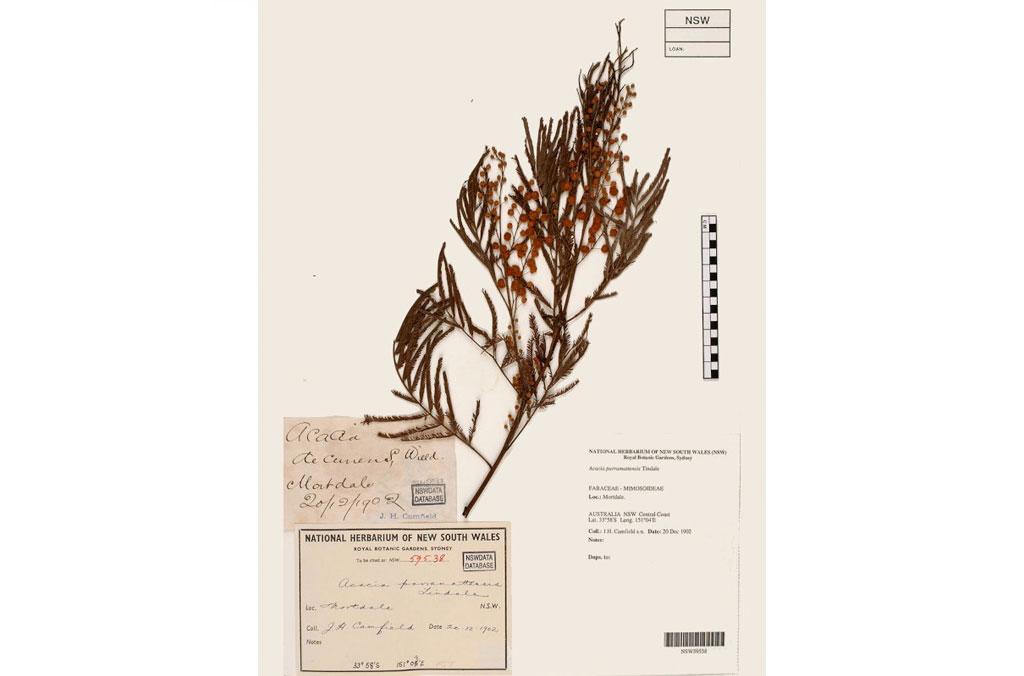

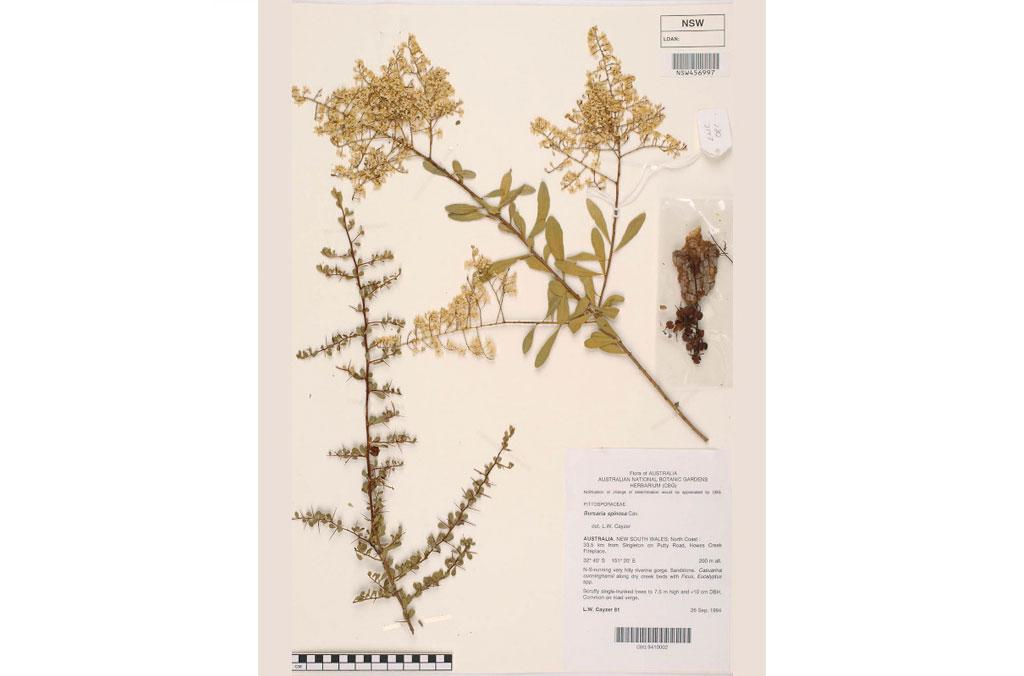

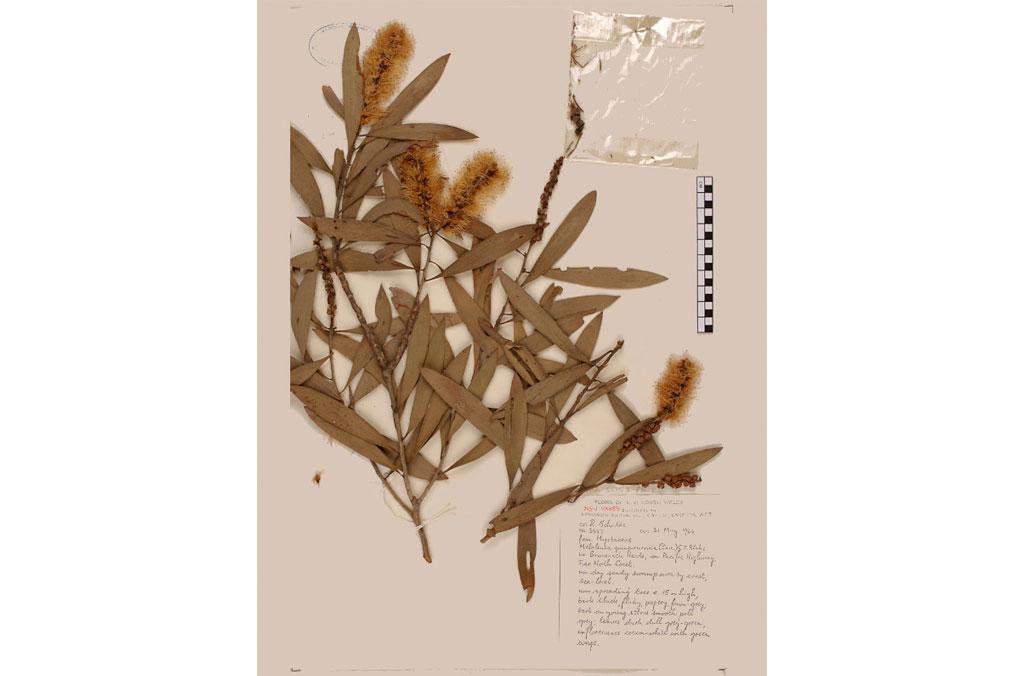

Below are Herbarium specimen sheets of Australian plants collected by scientists from the Royal Botanic Garden Sydney.

Activities: Seasons in Aboriginal culture

1. Read about plants

The image gallery highlights plants used as seasonal indicators. Read about them and choose your favourite.

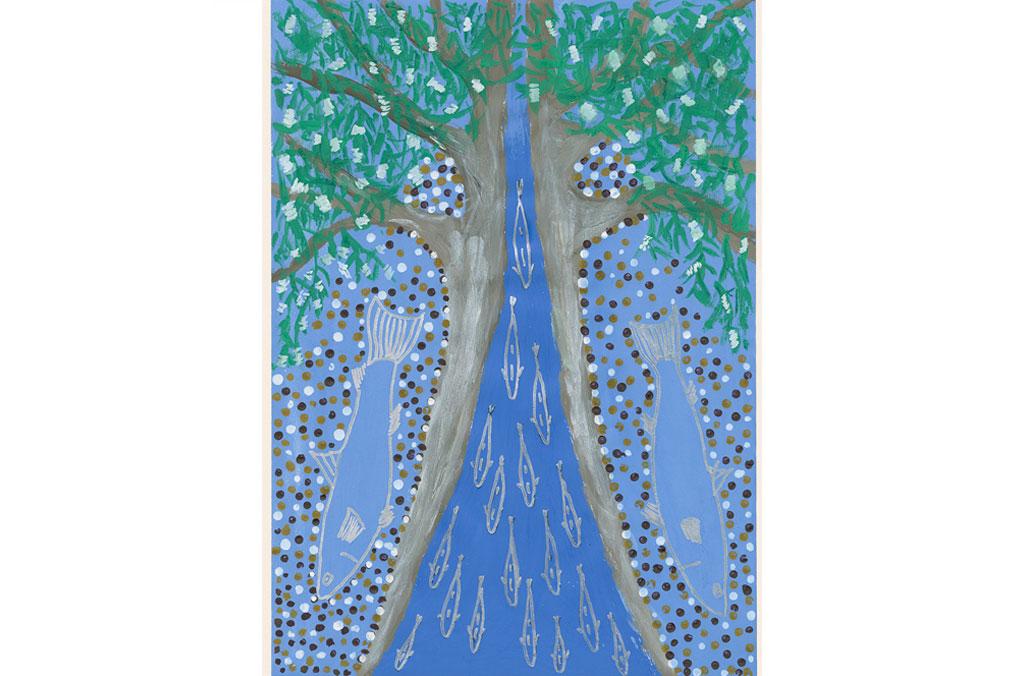

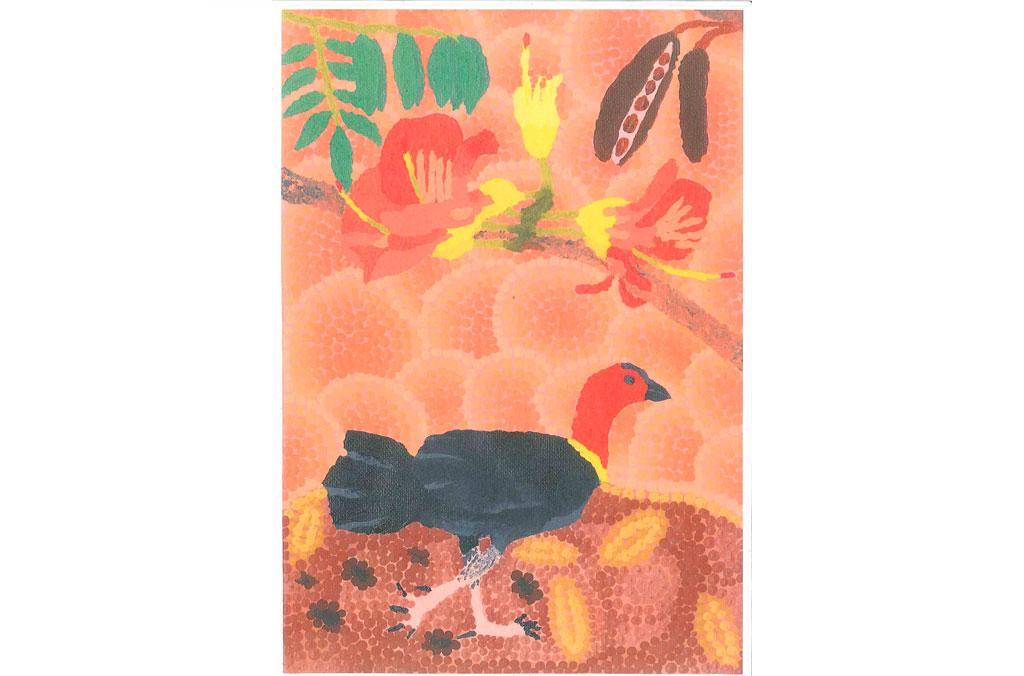

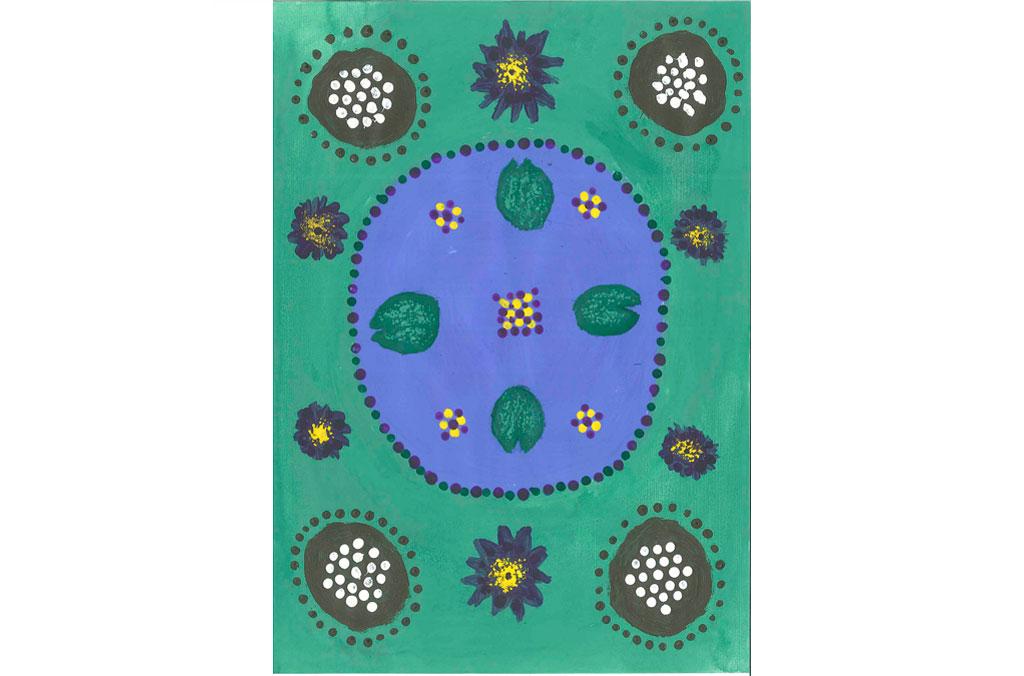

2. Create some art

Draw a story of your favourite showing the plant and what Aboriginal season it indicates.

Show your drawing to someone else and explain what the plant is, and what it means.

3. Examine the specimens

Look at the herbarium specimen sheets in the gallery above. Record whether they are flowering or not, as well as the time of year they were collected.

What other information have the scientists recorded on the sheet?

5. A plant life cycle

- Research, draw and label the life cycle of one of the plants you’ve collected which is indigenous to your area.

Gold-dust Wattle and Emu Eggs

For Wiradjuri people the emu was a valuable resource: they ate the meat, used emu oil as a medicine, feathers for decoration and large bones for construction.

Wiradjuri used the blooming of the Gold-Dust Wattle as a seasonal indicator for the time to collect emu eggs.

From late winter to early spring, strong westerly winds blew and the blossom fell, signalling the end of egg gathering as the chick will have formed inside the egg and begun to grow.

This practice of sustainability respects the emu cycle of life by leaving the developing chicks to hatch – this means the chicks can grow into adults which reproduce to hatch more eggs themselves, providing the Wiradjuri with a constant food source. Additionally, only adult male emus are killed for their meat leaving the females to lay the eggs.

Extending over a vast area in central New South Wales and bordered by the rivers Lachlan, Macquarie and Murrumbidgee, the grasslands running north and south to the west of the Blue Mountains, are the traditional home of the Wiradjuri.

Despite the vastness of their Country, the Wiradjuri were united by a common language, and strong ties of kinship and survived as skilled hunter–fisher–grower-gatherers in family groups.

The Wiradjuri’s close connection with the land provided them with valuable food and medicine resources such as grain from the grasses, kangaroo, possum, fish and shellfish, bats, and birds, particularly the emu.

Emu in the Sky

Wiradjuri people observed changes in the orientation of the Celestial Emu constellation in the night sky which they correlated to the breeding cycle of the emu: mating, laying and brooding of the eggs, and the hatching of the chicks. Learn more by watching this video.

Wiradjuri skystories of the Emu

Activities: Gold-dust Wattle and Emu Eggs

1. Listen to a story

Listen to the Wiradjuri Skystories and close your eyes and make the images of what is happening appear in your mind.

2. Dreaming art: Emu in the sky

Watch Wiradjuri Skystories about emu in the sky.

Make a stencil of an Emu with its legs either running, tucking up or without legs.

Make tiny coloured crayon marks all over the page in the area, outside the emu stencil, to represent the dust cloud within the Milky Way.

Paint wash in black over the whole page to create an image of the Emu in the Sky.

Remove the stencil.

Because you have painted the whole page and the stencil black (the night sky), when you lift the stencil you are left with a white silhouette of the emu. The paint will not adhere to the crayon marks which will appear as the stars/dust cloud of the Milky Way.

3. An emu life cycle

Research, draw and label the life cycle of an emu.

Label the parts of the life cycle when Wiradjuri would eat emu.

Why do they only eat the emu in this part of the emu life cycle?

How does this protect the emu?

Sydney Golden Wattle and fishing for Sea Mullet

The Gadi People (Gadigal) are the original inhabitants of the City of Sydney local area.

The territory of the Gadigal stretches from South Head around Sydney Harbour to the suburb known today as Petersham, including the land the Royal Botanic Garden Sydney sits on today.

The Gadigal’s close connection with the harbour provided them with a rich variety of plants and animals for food, with seafood from the harbour being a delicious local staple.

The Gadigal used seasonal indicators to guide which seafood was available and ready to be harvested at different times of the year. The flowering of the Sydney Golden Wattle (Acacia longifolia) indicated the season to fish for sea mullet.

Learn more about the cultural significance of Wattle by watching this video.

Activities: Sydney Golden Wattle and Fishing for Sea Mullet

1. Make observations

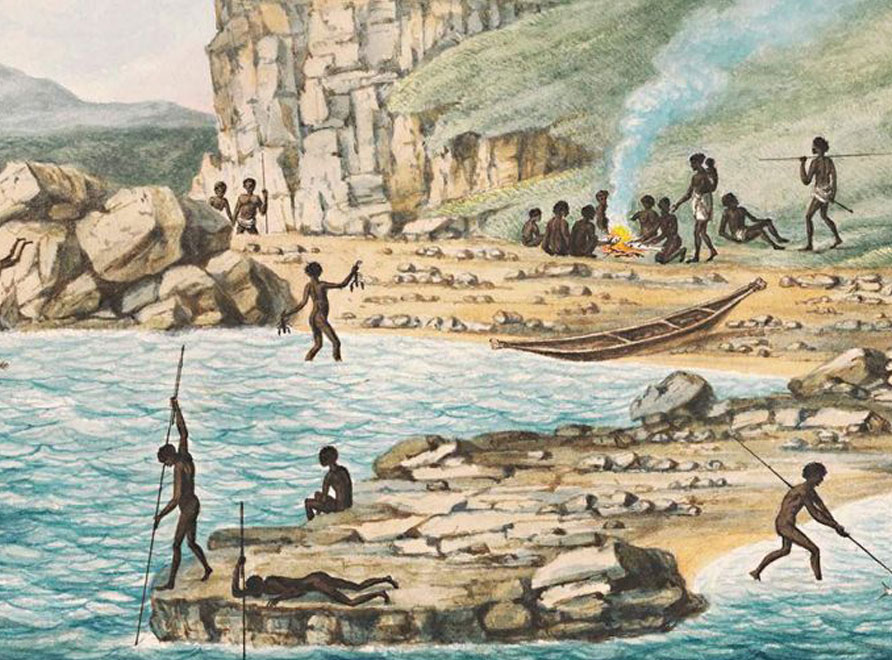

View the painting by Joseph Lycette.

Record the different types of food the people are hunting and eating and how they are catching them.

2. Make a map

Research the local Aboriginal people from your area.

What were the boundaries of their area?

What kinds of food did they eat?

Draw a simple map showing the area your local Aboriginal group inhabited and draw symbols on the map to show where they would have sourced different kinds of food.

3. Create some art

Watch the video ‘Wattle's Cultural Significance’.

Go outside and find natural resources to create an art display of this seasonal indicator. Include the sea mullet’s journey, the wattle flowering and the Gadigal catching fish with stone fish traps.

4. Examine the specimens

Look at the herbarium specimen of Sydney Golden Wattle in the image gallery.

What details are recorded on the datasheet?

Using a map of New South Wales, plot where the specimen was found.

Look at the specimen – is it showing flowers? What time of year was it collected? Does this match with the time of year Golden Wattles are recorded as flowering?