Making way for native plants

The invasion of African olive at the Australian Botanic Garden Mount Annan remains an ongoing challenge, but progress with clearing and regeneration is slowly restoring the natural ecosystem.

Horticulturists at the Garden continue to work at clearing weeds and invasive species across the Garden’s 416 hectares of diverse land, with African olive (Olea europaea subsp. cuspidata) being the prime offender.

African olive covers a large area of Cumberland plain woodland and Western Sydney Dry Rainforest at the Garden, along with a handful of resilient Acacia and eucalypts. Originally introduced to Australia as a hedging plant, this woody weed grows up to 15 metres high and can live for 100 years or more.

Tackling invasive species

Its canopy blankets the ground, prohibiting plant life and decimating wildlife habitat. African olive trees are so dense that heavy mulching machines need to be brought in to grind and chop them down to ground level. Even with this equipment, tearing down this invasive weed is a slow and tedious job.

Over the last 15 years, 55 hectares of African olive have has been removed. While the invasion front is being pushed away from the woodland, and the number of seeds spreading has reduced, there is still a lot of work to be done. About 30 hectares remains across the Garden.

This is only a fraction of the 4,000 hectares of African olive throughout Sydney’s south-west. With one tree producing more than 25,000 seeds per year, which are dispersed through bird droppings, every tree removed at the Garden ultimately contributes to plant diversity in the area.

Bird droppings carry African olive seeds that create halos of sapplings around native trees.

Clearing weeds is difficult and tedious, especially on a large scale, but progress has been made with African olive over the past few years.

John Siemon, Director Horticulture & Living Collection

Restoring the balance

Regenerating areas with native plants that have been squeezed out by African olive requires a coordinated effort involving Australian PlantBank scientists, horticulturists from the Garden and the local community. First, the area is mulched, then the weed is left to sprout again before being treated. It is only after this that native species can be reintroduced.

Plants are grown in the Garden’s nursery from seed gathered by the Field Collection Team, before being planted in their natural habitat. Each section undergoing regeneration has a 10-year plan, starting with the first step of mulching, to re-establish plant diversity back in the landscape.

After the first few years of the plan, ongoing maintenance is required to fully reclaim the landscape, so it can be used for conservation, horticulture, research or recreation. Without this careful maintenance, African olive will re-establish within a few years.

As native plants are reintroduced to the Garden, native birds are returning, wallaroos have grass to eat, threatened orchids are thriving and rare plants can be researched in their natural habitat.

Areas of the Garden that have been rehabilitated, with ongoing treatment and maintenance, are now a benchmark for controlling invasive species.

As native plants are reintroduced, native birds are return to their natural habitat at the Garden.

Related stories

Three carnivorous plants to care for during the cooler seasons.

Three carnivorous plants to care for during the cooler seasons.

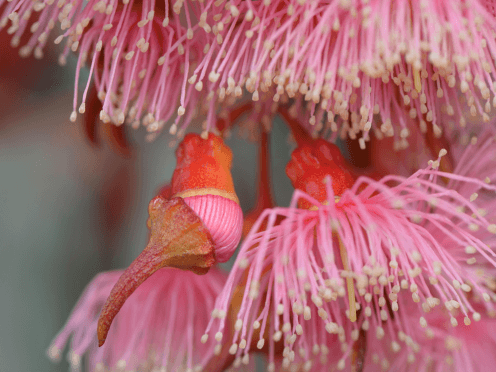

Eucalypts or gum trees are one of Australia’s most iconic plants. The scent of their oil alone evokes the bushland.