Five days and five discoveries on Lord Howe Island

Chief Scientist Professor Brett Summerell shares his highlights and learnings from a return to the tiny island off Australia’s east coast

In early June, I was lucky enough to to take a field trip to the tiny but treasure-filled Lord Howe Island for five days, located east of Port Macquarie in the Tasman Sea. I was struck not only by the island’s native beauty, but the efforts to protect it and the looming threats on its doorstep.

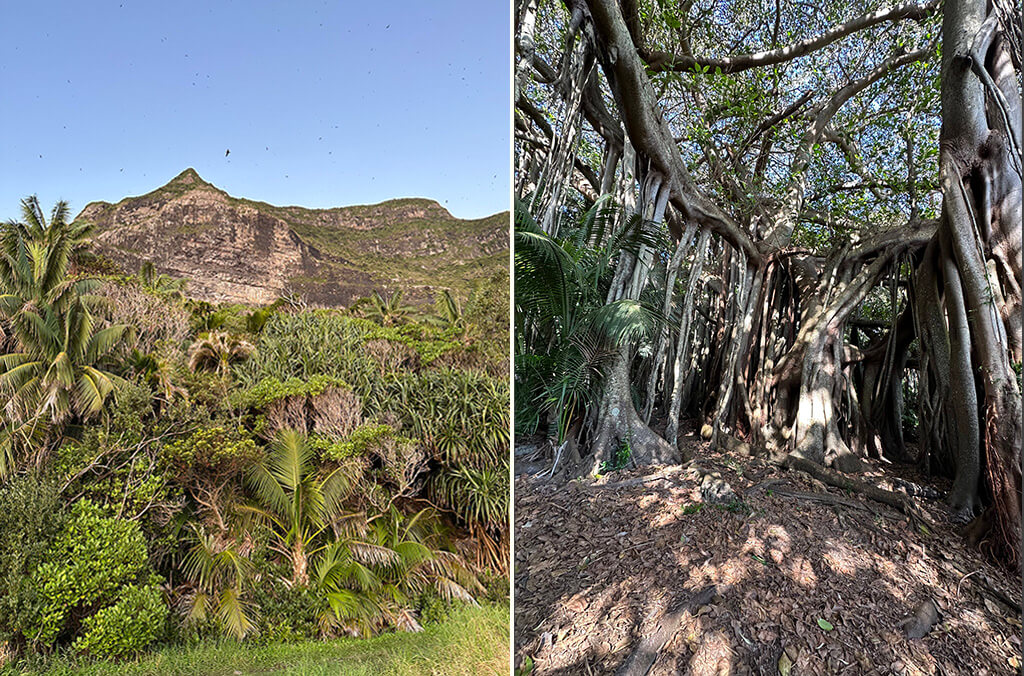

The subtropical plants and rainforests of Lord Howe Island are captivating. Credit: Botanic Gardens of Sydney

1. A plant paradise

This island – only about 16km squared in size – is an incredible place that resembles something from Jurassic Park with its towering peaks and aqua-tinged shores. Its forests are full of unique flora and fauna found nowhere else in the world, reflected in its status as a UNESCO World Heritage Site of global natural significance.

For such a small area, it is home to a surprisingly large number of distinct plant species – more than 100 unique species and subspecies thrive in its subtropical forests. Some plants are household names and are grown around the world, such as the two species of kentia palms trees (Howea forsteriana and H. belmoreana). These trees dot the shorelines with their rugged deep green palms and seem to embody the tropical feel of the island.

The Lord Howe Island banyan (Ficus macrophylla f. columnaris) is one of my favourites. It is a magical, magnificent fig that grows staggering tall and covers vast areas of the island. Its climbing, limbering roots wrap around its thick trunk that reaches up to the very tops of the rainforest, housing all kinds of native mammals and birdlife.

The fauna and flora on Lord Howe Island are precious and strict measures are taken to protect them. Credit: Botanic Gardens of Sydney

2. Projects to protect native flora and fauna

Sadly, not all natural areas on the island have remained untouched and unwaveringly pristine. For much of this place’s recent history there have been extinctions of its native animals, especially birds. Predated upon by introduced feral animals (including pigs, goats, cats, rats, and mice), populations of native fauna plummeted with the previous lack of control of introduced species.

Though these feral animals thrived in the past, there are now enormous efforts to eradicate them and reinstate the island’s natural biodiversity. The island’s Rodent Eradication Project has seen one of the largest efforts worldwide to eliminate rats and mice and it has declared the island free of rodents – no mean feat.

This recent success has created a major positive impact on both the flora and fauna, helping many native species to bounce back in droves. The most noticeable has been the Lord Howe Island woodhen, which is now so common it’s something of a constant clucky companion when travelling around.

3. A whole new level of biosecurity

As soon as the plane wheels touch the ground of Lord Howe Island and you alight at the airport, a hypervigilant biosecurity force emerges. Detective dogs bound over to sniff you for any trace of plant or animal products, followed by mandatory foot baths and the sanitisation of shoes to fend off any exotic diseases hitching a ride on your boots.

These strict and necessary procedures extend well beyond the airport. Almost every sign on the island yields constant disease and pest control reminders. Each walking trail begins with a biosecurity station, more foot baths and disinfecting of shoes, packs, and clothing. It’s a laborious but effective precaution to protect the island’s rarest lifeforms.

Biosecurity alerts warning about the spread of Myrtle Rust are found across the island. Credit: Botanic Gardens of Sydney

4. An infamous fungal disease

Though the Lord Howe Island board are using almost every measure to safeguard plants and wildlife, even the most rigorous biosecurity measures can’t stop tiny, deadly spores blowing off Australia’s east coast.

Earlier this year, the deadly Myrtle Rust pathogen was detected for the second time. The last detection of this micro-organism was in 2016, when ornamental plants vulnerable to the disease were showing suspicious small purple spots their leaves – the first sign of infection. A major operation was launched to fend it off, removing any infected plants and soils and banning public access to all trails on the island in the process.

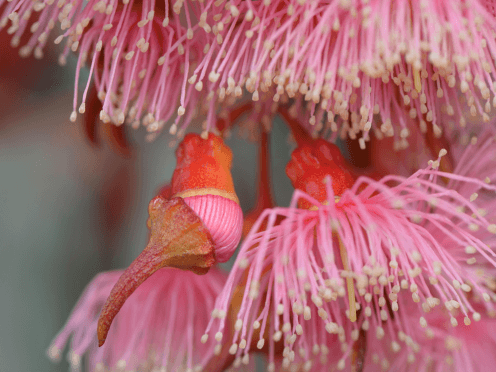

There are five species of native plants in the susceptible Myrtaceae family on the island – two species of mountain rose (Metrosideros nervulosa and M. sclerocarpa), a paperbark tree (Melaleuca howeana), a tea tree (Leptospermum polygalifolium subsp. howense), and scalybark (Syzygium fullagarii), a large lilypilly.

If Myrtle Rust were to take hold, these plants would be facing an almost unstoppable fate. This time, authorities have once again swooped in to prevent this new breakout, significantly reducing the likelihood of the disease establishing a foothold. But it won’t be the last time it’s found here.

The island is only 600km east from Port Macquarie – a relatively small distance for untraceable spores to travel in from the coast. Only the persistent, constant surveillance of new symptoms in plants will be able to keep this deadly disease at bay.

The looming threat of further Pytophthora hangs over Lord Howe Island. Credit: Botanic Gardens of Sydney

5. A silent threat

Just as Myrtle Rust's potential spread threatens the plants of Lord Howe Island, another plant disease even more untraceable lurks beneath the surface. Phytophthora cinnamomi, commonly known as ‘root rot’, is a micro-organism that could have a devastating impact. This pathogen takes hold of a plant when it’s waterlogged, slowing its growth, turning its leaves pale until they fall to the ground, eventually destroying the plant.

Root rot can lurk for months or years undetected in dry weather. Adding to its menace, its spores and other structures can easily be spread by almost anything, from the soil stuck to shoes to the mud trapped inside of a vehicle tyre. It is a silent killer that has single headedly wiped out millions of plants and trees across Australia.

A few years ago, my team and I detected the disease in a fruit tree on the island, quickly prompting the establishment of a quarantine exclusion zone. Once root rot takes hold of a soil it is impossible to remove, no amount of unearthing will prevent it from spreading; the only key is prevention.

After the discovery, our PlantClinic team searched the island extensively for any sign of its spread, taking soil samples along tracks, foot bath stations, nurseries and meticulously searching the original site of infection.

Our soil samples are being analysed at the invasive intruder’s PlantClinic. To detect any lingering disease, the soil will be flooded with water to promote the growth of Phytophthora and a variety of DNA based tests can extract it if found.

While it’s too early to predict the outcome of the tests, our results will guide the future approach to stopping any trace of diseases decimating this special sanctuary of a place.

Lord Howe Island is as precious as it is vulnerable. I encourage anyone to visit and be awe-struck by its wondrously tall trees, pristine shores, and friendly woodhens while respecting the measures in place to keep its distinctive ecosystem thriving.

The island’s careful regulations reveal a valuable lesson in maintaining the biodiversity of on our own shores in Australia. We can all do out it to protect our native species and stop the spread of these invasive intruders. Any time you venture into the bush, rainforest, or forest area, make sure to spray your shoes with 70% methylated spirits to maintain our wonderous land.

Related stories

Three carnivorous plants to care for during the cooler seasons.

Eucalypts or gum trees are one of Australia’s most iconic plants. The scent of their oil alone evokes the bushland.

Immerse yourself in cool climate mountain maples, starry nights and magical mountain heights for a weekend roadtrip like no other.