A decade of saving species at Australia’s biggest plantbank

The Australian PlantBank is commemorating 10 years of protecting Australia’s unique native flora from going extinct.

Discover how a humble collection of plant specimens in tiny jars in a basement became an award-winning facility storing thousands of species as we look back on the facility’s legacy, the achievements of its staff, and the vital plant conservation role it will play into the future.

The cutting-edge home for plant conservation

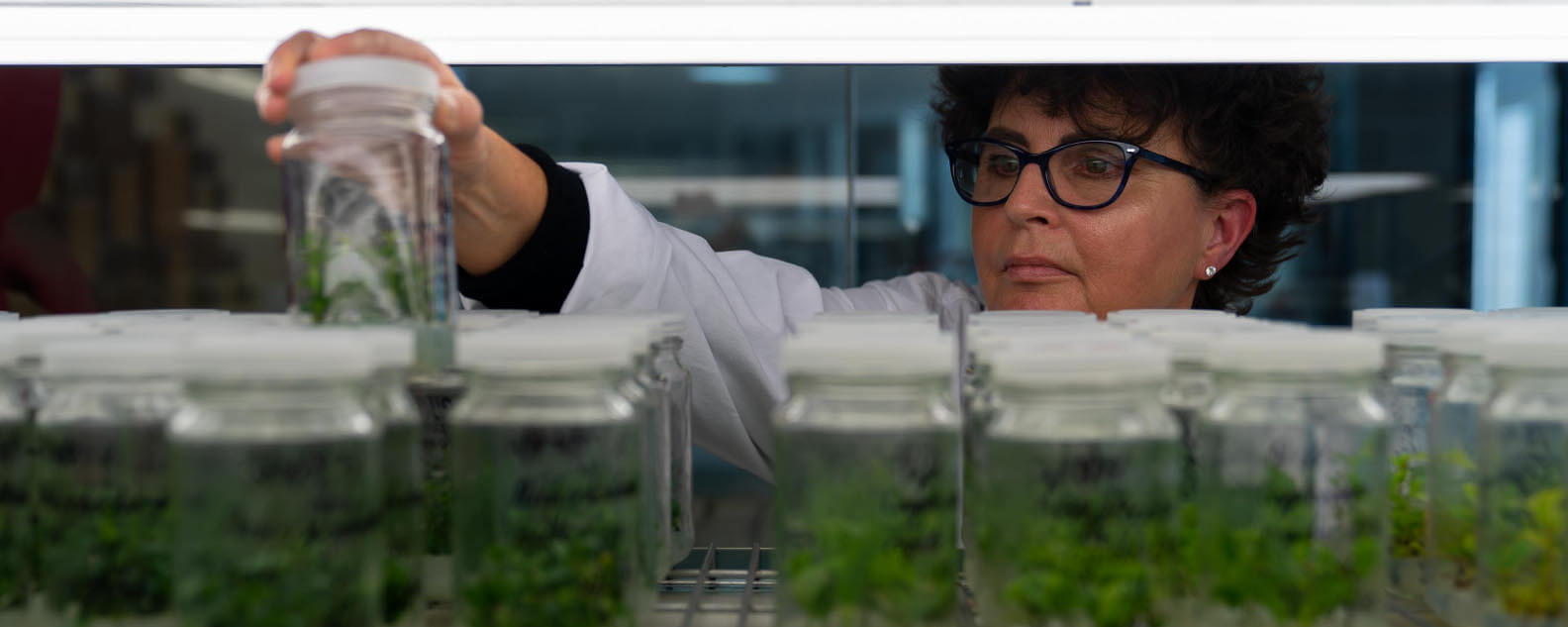

At the Australian PlantBank, the largest collection of New South Wales’ native plant seeds in existence are stored in state-of-the-art facilities at the Australian Botanic Garden Mount Annan. Walk in cool rooms, drying rooms, tissue culture labs and even cryogenic freezers hold thousands of seeds and other plant material for scientific research, education, and propagation. Ultimately, these important collections are an insurance policy – ready to be germinated and grown for replanting if their wild counterparts become endangered, or worse, extinct.

History in the making

In the early 1980s, the scientists at the Royal Botanic Garden Sydney would collect plant specimens and store their seeds inside cloth bags, envelops and tiny glass jars, stacking them in the basement of the former National Herbarium of New South Wales.

Used for growing in the Botanic Gardens and a part of an international seed exchange programs, seed banking – a practice where seeds are stored to preserve genetic diversity for the future – was becoming more pertinent.

Chief Scientist & Director of Science, Education and Conversation at the Botanic Gardens of Sydney, Professor Brett Summerell, has seen PlantBank from its origins as a makeshift seedbank.

“When we first started collecting seed, we would store specimens in the basement of the herbarium, but the seeds did not keep well in the Sydney humidity and consequently were only useful for a short period. We even used a mini-fridge at one point to keep the rarest species in cooler conditions, but as you can imagine we quickly ran out of room,” says Professor Summerell.

To store most seed properly, a plant’s seed-bearing fruits need to be dried and the seeds removed. The seeds need dry and cool conditions to remain in a state of ‘suspended animation’ with minimal metabolic activity.

A collection of dry native seeds at PlantBank, located at the Australian Botanic Garden Mount Annan. Credit: Botanic Gardens of Sydney.

''A lot of plant seeds need very specific temperatures and humidity to stay viable for propagation. We didn’t have the resources or the funding to build a modern seedbank, but we made sure to keep what seeds we could so a collection could begin.''

Professor Brett Summerell

By the mid to late eighties, the team opted to move the seeds to the Australian Botanic Garden Mount Annan, which would help generate a living collection for the newly established botanic garden. This time, the team were determined to structure a more modern seedbank, repurposing retired commercial drink fridges for storage and adopting tissue culture technology.

“We bought these old soft drink fridges from a wholesaler that were in good condition, hoping it would at least provide enough space for us. Thankfully it worked, we still have some of the seeds from those fridges to this day,” said Professor Summerell.

Through the nineties, the team continued collecting and propagating a vast array of species – including the tissue culture of natives like Waratahs and Flannel Flowers. In 1994, the Wollemi Pine was discovered in the Blue Mountains and heralded as the botanical discovery of the century. The team were able to capture seeds of this species, which has a direct lineage dating back over 140 million years, studying the extraordinary findings and securing its DNA.

NSW Seedbank scientist Dr Cathy Offord in the Wollemi National Park gorge collecting material from the only population of Wollemi Pines in the wild. Credit: Jaime Plaza/Botanic Gardens of Sydney

The NSW Treasury granted funding for a major upgrade of what was then known as the NSW Seedbank to support conservation of NSW native species, including threatened species.

In 2003, a partnership with Kew Garden’s Millennium Seed Bank Program also began, supporting an expanded state-wide seed collecting program and increased capacity for seed testing and research, as well as further collaboration with other Australian conservation seedbanks.

More dryland and orthodox species, like acacia’s and eucalypts, were collected as technologies increased. A zig-zag aspirator for processing and cleaning seed was installed and the team expanded germination capacity for propagating more species.

At the turn of the century technology continued to expand and x-ray machines, digital microscopes and even cryostorage research was introduced, storing the seeds at ultra-low temperatures of -196°C. Huge scientific milestones were made throughout the early 2000s with alpine seed research, orchids and fungi cryopreservation, and the screening of rainforest seeds for desiccation tolerance. The team restored its on-site area with local species, after clearing the invasive African Olive.

In 2011 funding was finally secured to construct the Australian PlantBank and in 2013 it was officially opened. Today, the Australian PlantBank employs dozens of scientists, storing thousands of Australia’s native seeds and hosting an invaluable living collection of plants for research, conservation and restoration of the state’s plants.

The Australian PlantBank is an award-winning facility, storing the largest collection of New South Wales’ seeds. Credit: Simone Cottrell/Botanic Gardens of Sydney.

Saving orchids from extinction

With roughly a quarter of plant species facing extinction worldwide through the impacts of habitat destruction and the effects of climate change, the Australian PlantBank’s odyssey ranges from gigantic forest trees to delicate flowers, including rare terrestrial orchids.

The Terrestrial Orchid Conservation Program, with funding from the NSW Government’s Saving our Species program, has tested even the most patient scientists at the Australian PlantBank.

“They’re all tricky to grow, but one species, the Kangaloon Sun Orchid (Thelymitra kangaloonica), which comes from the Southern Highlands, we have spent the last four to five years trying to get to grow,” says Conversation Scientist, Dr Zoe-Joy Newby.

“I finally germinated one seedling which was sown over soil collected from the wild population and have recently germinated seed (without a symbiotic fungus) on a really high nutrient medium - it took 11 months for a few tiny seedlings to turn green.”

“And that's just one species. We've got another species, a Pretty Beard Orchid (Calochilus pulchellus) which we've just never been able to germinate. There’s one published record of Calochilus germination and the authors concluded that their seeds have less than 1% viability. They’re just really challenging and nobody really understands why.”

To successfully germinate orchids and help them be translocated into the wild, Dr Zoe-Joy and her team must work through a painstaking process.

“Orchid seeds themselves are incredibly small, they’re dust like,” says Dr Zoe-Joy. “The seeds only have the embryo (where the DNA is) and the seed coat, unlike most other plant species which also have a food supply. For the seed to sprout, they need to be infected by a symbiotic fungus, which essentially feeds them.”

“Some orchid capsules produce thousands of seeds but we may only germinate about 10 plants from that, if we’re lucky.”

Dr Zoe-Joy

The team not only need to harvest a rare seed supply but also find an appropriate fungus – either extracting it from the orchid tissue, its root system or luring it from the soil with a seed bait.

“Each fungal strain we collect must be tested to see if it gets the target orchid growing. Each strain is set up individually with seed and then we incubate them in the dark for months, until something hopefully starts to grow.”

If its root system develops and a leaf does form, then they’re big enough to go into the light.

Scientist Dr Zoe-Joy Newby hand pollinating a Smooth Burr orchid (Cadetia taylori). Credit: Michael Santos

More repotting, more monitoring, and more patience is the key to translocating to the wild.

“These young plants are very delicate and very, very precious. We wouldn’t usually anticipate flowering for at least two to three years."

“If that does happen, we let them go through their natural cycle and eagerly await for them to re-emerge the next season. And then you know that you've really, truly been successful in propagating them when they come back out the next year.”

“It’s a drawn-out process, but incredibly rewarding when you do succeed.”

The scientists have worked on germinating eight terrestrial orchids species in total, protecting this irreplaceable species that are the cornerstone of unique beauty in Australian flora.

Sowing the seeds of the future

With threats to native plants like new diseases and global warming intensifying, the Australian PlantBank is an essential safeguard to our unique plant life. Kew’s latest State of the World’s Plants and Fungi report sounds the alarm on the sheer increase of plant life now facing extinction; 3 in 4 of the planet’s undescribed species, including a staggering 77% of undescribed vascular plants, and 45% of known flowering plants.

With the onset of El Niño and a potentially dry, hot summer and severe bushfire season, the Australian PlantBank’s collaboration with the Rare Bloom Project is timely. The project aims to improve conservation outcomes for 120 of Australia's native wildflowers from fire affected and high-conservation-value areas across Australia.

As the Head of Australian PlantBank Research, Dr Cathy Offord, puts it: “seedbanking and research into threatened species is becoming more crucial with every passing day. Some of these seeds are a last line of defence for native species if things go wrong in the wild.

“Over the past decade, we’ve expanded our studies to rainforests, researched new diseases like Myrtle Rust, and established the translocation of threatened species, all while adopting new methods like DNA sequencing and new drying technologies.”

The Australian PlantBank uses seedbanking, which involves collecting and storing seed from plants so there’s an alternative source of genetic material. Credit: Botanic Gardens of Sydney

Delving into PlantBank’s history and achievements, Professor Brett Summerell emphasised its future as an invaluable resource.

“The last few years have seen more extreme weather and new deadly pathogens destroy some of our most vital plant life in Australia. The Australian PlantBank is one of the few institutions that can help mitigate and restore these areas that are still recovering or at risk.”

“We have so many challenges ahead of us, with illegal collection, dwindling pollinators and more extreme weather on the cards – PlantBank’s vital role in conserving our species can’t be overstated.

From travelling across the country to collect seeds and other plant material to translocating threatened plant and unique species like the Geebung (Persoonia), the work of the Australian PlantBank is critical. You can explore more about the key projects taking place at this fascinating facility on the frontline of saving our flora.

Director of Horticulture John Siemon, Head of Australian PlantBank Research Dr Cathy Offord, Manager Seedbank Nathan Emery and Chief Scientist Professor Brett Summerell. Credit: Glenn Smith/Botanic Gardens of Sydney

The Australian PlantBank:

Currently stores more than 12,500 collections of seed from a diverse range of plant communities across Australia.

Maintains and researches seed from 48% of the more than 6,000 seed bearing plant species that occur in New South Wales. Many species are represented by multiple collections from different populations across the state.

The Australian PlantBank collections include 455 species (72%) of the plants classified as under threat by the NSW Biodiversity Conservation Act. Also, more than 20% of species that are protected under the Federal Environmental Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act.

Acknowledgements

The team at the Australian PlantBank are supported by partners, including the NSW Government’s Saving our Species program, the Australian Seed Bank Partnership, HSBC, Transgrid and The Ian Potter Foundation. Visit the Australian PlantBank.

Seeds stored in the old Herbarium at the Royal Botanic Garden Sydney in the 1980s and specimens in soft drink fridges at the Australian Botanic Garden Mount Annan during the 1990s. Credit: Botanic Gardens of Sydney

Staff at the NSW Seedbank, prior to the Australian PlantBank’s opening. Credit: Botanic Gardens of Sydney

An xray of an acronychia plant and scientist Karen Sommerville using cryostorage to preserve plant specimens. Credit: Botanic Gardens of Sydney

Seed embryos at PlantBank, located at the Australian Botanic Garden Mount Annan. Credit: Botanic Gardens of Sydney.

The Australian PlantBank’s opening day in 2013 at the Australian Botanic Garden Mount Annan. Credit: Botanic Gardens of Sydney

Director Horticulture & Living Collections John Siemen shows school children through the Seed Vault at the Australian PlantBank. Credit: Botanic Gardens of Sydney

NSW Seedbank’s early beginnings at the Australian Botanic Garden Mount Annan. Credit: Botanic Gardens of Sydney.

The Australian PlantBank is Australia’s biggest seedbank. Credit: Botanic Gardens of Sydney

Related stories

Bunga Bangkai (Indonesian), Titan Arum or Amorphophallus titanum has the biggest, smelliest flower-spike in the world. It flowers for just 24 hours, once every few years… and in January 2025 one bloomed at the Royal Botanic Garden Sydney. Named Putricia by staff at the Botanic Gardens of Sydney, she quickly captivated people from all over the world, writes John Siemon, Director of Horticulture and Living Collections.

The legendary Wollemi Pine (Wollemia nobilis) has captivated the world since its discovery in the Blue Mountains in 1994. Three decades later, its survival story isn't over yet with the critically endangered conifer still at risk of extinction.

New developments in machine learning are allowing huge datasets to reveal changes in plants. Scientists at Botanic Gardens of Sydney have harnessed these advancements to look at Australian eucalypt species, unveiling their transformation over millions of years.