You are in Cadi: The traditional lands of the Gadigal

The Traditional Custodians of the land on which the Royal Botanic Garden Sydney stands are the Gadigal. The Gadigal Peoples have a strong and significant connection to these lands, waters, sky, flora and fauna.

Taking time to reflect

The natural wonders of the lands they care for were long known to the Gadigal. However, a place that was unrecognisable and more like England sprang up following the arrival of the First Fleet in 1787, bringing with it dire consequences for the First Nations communities of the area, Cadi was irrevocably changed. Now in the 21st century, we pause to reflect and commemorate tens of thousands of years of First Nations Peoples' presence on this land.

Who are the Gadigal?

The Gadigal are the traditional custodians of the lands located in what is now the city of Sydney. Before being named Sydney in the 1770s, the land was originally called ‘Cadi’. ‘Gal’ means people, so the Gadigal literally means the people of Cadi.

The word Cadi comes from the grass tree species Xanthorrhoea, a native plant that local First Nations communities would make sections of spear shaft from the stems and glue together with the resin.

The Gadigal are part of a wider group known as the Eora, who numbered roughly 1,500 individuals in the wider coastal area when the colonisers arrived. There were thought to be 29 communities in the Sydney region, with the Gadigal making up around 100 people.

The inhabited area of Cadi included the cove known as ‘Warrane’ and what is today’s Sydney CBD and Royal Botanic Garden. As a coastal community, the Gadigal were dependent on the harbour for the majority of their food.

Much of what we know about the pre-contact culture and ceremonies of First Nations peoples are from a colonial perspective.

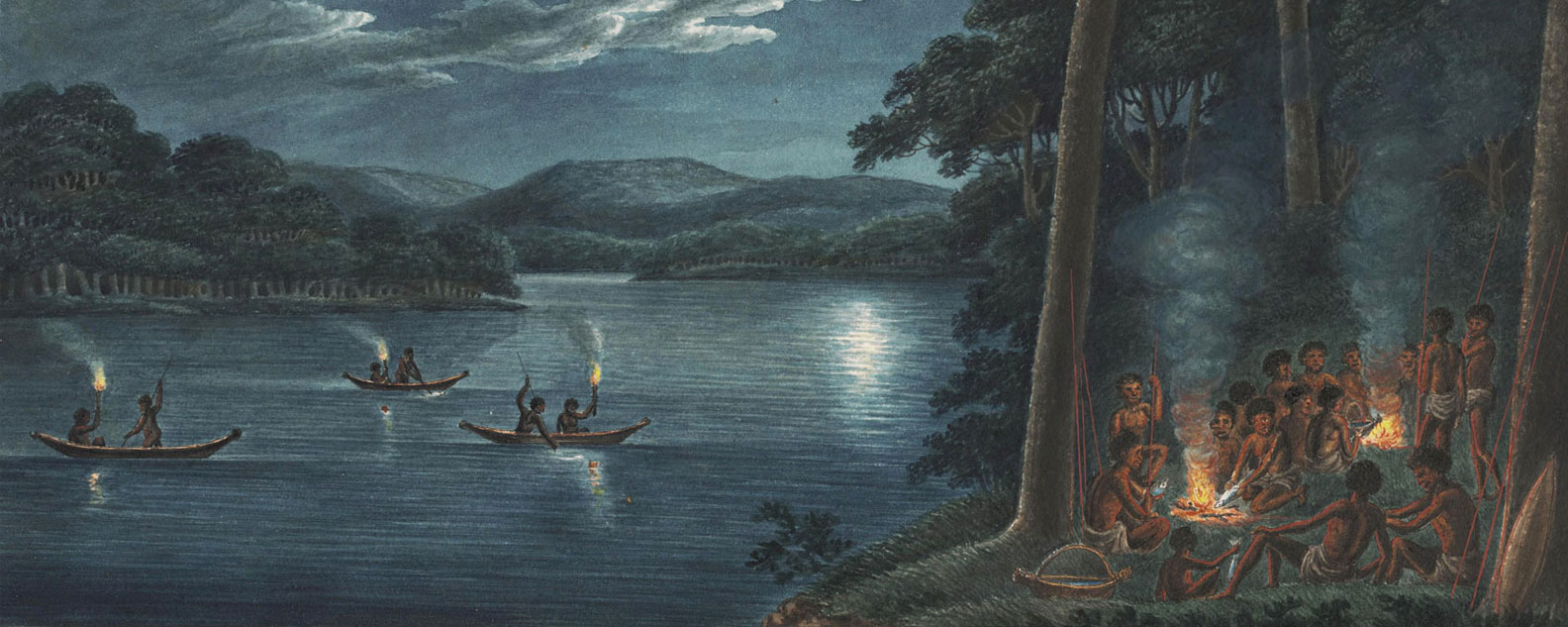

Thomas Watling's drawings of First Nations ceremonies are thought to have been recorded in the Cadi area.

A ceaseless connection to the land

The Gadigal had learnt to work in harmony with conditions that might seem harsh to the uninitiated observer – dense bushland, nutrient-poor soil and erratic rainfall.

Gadigal women were revered as highly skilled fishers, swimmers and divers. Warrane was an important gathering place and canoe route, providing food to the 29 surrounding communities. As well as being skilled fishers, the Gadigal hunted possums, emu, kangaroo and reptiles.

A painting of First Nations men and women fishing circa 1790.

Nature provides

Gadigal tools and weapons were made from the plants and animals of the area: fishing lines were made from the fine silk thread of the golden orb spider's web, dried lomandra leaves, palm tree husk and kangaroo sinew.

In addition to the waters of Woccanmagully (Farm Cove) being a special hunting place, these waters were also ceremonial areas where rituals were enacted.

Sustainability: A way of life

Sustainability was at the core of all of the Gadigal's actions and respecting the food that the lands and waters provided ensured its ongoing availability, avoiding waste was a priority. Shells were placed on middens, creating a linear chronology that showed the next people who came along what had been taken, prompting them to choose another food. In this way, the Gadigal ensured the waters of Woccanmagully remained plentiful.

A example of the kinds of food collected by First Nations communities of the area.

Arrival of the First Fleet

When the First Fleet arrived in 1787, the Cadi was irrevocably changed, with land cleared for the First Farm, Government House farm and Sydney Town.

The early stages of British settlement, 'Sydney Town', circa 1790.

The clearing of the land

An area studded with towering eucalypts, angophora and banksia that had stood for hundreds of years was felled to make way for the First Farm.

In some of the earlier convict accounts, it was noted that when they attempted to cut down the trees, their tools broke and the tree trunks had to be blasted out of the ground with gunpowder.

"It will scarcely be credited that I have known twelve men employed for five days, grubbing out one tree."

A report from John White during the establishment of the colony.

Species' that had provided sustenance, tools and fibres to First Nations communities for thousands of years, evolving over millennia to thrive in the conditions of the Great Southern Land were felled. The ongoing clearing had consequences for the animals that the Gadigal hunted and they were driven out from the area as their habitats were displaced.

The destructive period immediately following the first encounter would have been shocking for the First Nations communities, with its blatant disregard for spiritual protocols and customs. Fish stocks were depleted at an alarming rate and slow-growing Cabbage Tree Palms were removed to build houses.

Painting of the raising of the British flag, 1788.

Gadigal Strength and resilience

The frustrations encountered by the First Fleet during the establishment of the colony were minuscule compared to the difficulties imposed on the First Nations Peoples. The occupation of the land by the British led to the introduction of new diseases that would prove tragic for the Gadigal.

The spread of smallpox in 1789 is estimated to have killed 53% of the First Nations population and it is claimed that only three Gadigal remained in 1791. However, it was suspected that some may have dispersed out to the Concord area to escape the epidemic.

British troops practicing naval action at Yurong (Mrs Macquaries Point).

Culture prevails

Despite the pressure from disease, land clearing, contamination of water sources and depletion of food caused by colonisers, the Eora peoples were unrelenting in their adherence to their ceremonial, cultural and spiritual practices. The importance of the ceremonial sites on which the Royal Botanic Garden Sydney now occupies, cannot be overstated.

Adding insult to injury, 1882's dramatic Garden Palace fire on the grounds of what we now know as the Royal Botanic Garden Sydney saw the loss of irreplaceable material culture amassed by the colonisers as they travelled through First Nations communities up and down the Eastern Australian coastline.

The Garden Palace before the fire.

Cadi now

To acknowledge that the Royal Botanic Garden Sydney stands on Gadigal lands, the Cadi Jam Ora – First Encounters Garden and First Farm was opened in 2001, Cadi Jam Ora is translated as 'I am in Cadi'.

The Cadi Jam Ora – First Encounters Garden and First Farm explore the relationship between people and plants on the site of the first frontier between the Gadigal and the British colonisers. Visitors to the garden are taken on a journey through the Gadigal peoples' past, present and future set amongst both native and exotic plantings.

The Cadi Jam Ora timeline.

Jonathon Jones: barrangal dyara

Reconnecting the public with that pivotal time, Wiradjuri/Kamilaroi artist Jonathan Jones worked with the Garden's staff to create thought-provoking sculptural and aural installations in the Royal Botanic Garden Sydney in 2016. 'barrangal dyara' (Gadigal for 'skin and bones') was installed where the Garden Palace stood before the great fire that destroyed irreplaceable sacred objects that belonged to First Nations communities along Australia's east coast.

The project was Jones’ response to the immense loss felt following the destruction of the culturally significant items. It represented an effort to commence a healing process and was a celebration of the survival of the world’s oldest living culture. Thousands of bleached white shields marked out the shape of the Garden Palace on the grounds of the Garden.

Jonathon Jones: barrangal dyara (2016) when viewed from above, thousands of white shields mark the shape of the Garden Palace.

Enjoy a taste of First Nations culture in the Garden

Book a place on one of the Royal Botanic Garden’s Aboriginal Bush Food Experiences or join an Aboriginal Heritage tour to learn more about the diverse history of these lands and their peoples. If you'd prefer to move at your own pace, you can always time travel with the richly illustrated interpretive signage in the Cadi Jam Ora Garden.